|

|

|

|

|

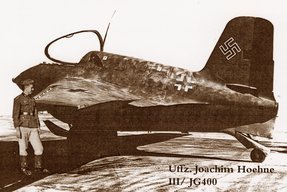

Joachim was born in Leipzig, Germany, as the youngest of three children to Otto and Ursula Hoehne. His mother was Polish and Catholic. His father was an officer in the German air service in World War I, when pilots usually came from the aristocracy. "Somehow they didn't have enough intelligent daredevil people of blueblood that wanted to be shot down," he says. A fighter pilot, his father slept in the same barracks with the famous Manfred Von Richthofen, better known as "The Red Baron." The day Richthofen was shot down he was wearing underwear he had borrowed from Joachim's father. "He died in my father's underwear," Joachim quips. His father was shot down, too, but never received the Pour le Merite, better known as the Blue Max. After the war the family lived in several places, including Warsaw, Brussels, and Austria where his father worked as a factory engineer. After Adolph Hitler came to power, his father trained pilots secretly for the German air force. "This was all hush-hush," he says of the training. "All I do know is that he always had a bunch of young men coming in and I had to leave," he says. Joachim remembers Hermann Goering visiting with his father. "I never did like the fellow," he says. Goering would become commander of the German Luftwaffe, while Joachim's father rose father rose to the rank of major general in World War II. At age 14 Joachim was selected as a company leader in the Hitler Youth organization. He was chosen, he says, because he was a good boxer and could whip most of the boys. He recalls attending a two-week Hitler Youth training camp during a summer vacation. "They fill you full of propaganda and give you basic training like you're in the army," he says. They also "had a lot of political crap we had to swallow." At the same time, Joachim served as an alter boy in the Catholic cathedral where he worshipped with his mother. Once, in defending the pope, he defended the pope, he was thrown in jail where he remained for a summer. His father came and got him out. "I told the Hitler Youths goodbye. I didn't want no part of them," he says. A few months he was drafted into an antiaircraft unit "under the umbrella of Hitler Youths," he says. "We had to wear the swastika arm band, which none of us liked, you know. We felt like we were already soldiers." He was number one gunner on an 88-mm anti-aircraft gun in Kassel, Germany. He recalls watching German fighters shoot down British Lancaster bombers. The debris of one downed bomber nearly fell on him. Joachim volunteered for the air force. Because Germany was short on fuel, he was trained in a glider, and completed about fifteen hours of flight. He then volunteered for training in a Messerschitt ME-163 Komet, a rocket-powered fighter aircraft. He wore flameproof protective clothing. At the same time, he says, the German air force had the ME-262 Schwalbe, the world's first jet-powered aircraft. "Why in the world didn't they stay with the ME-262 and put a whole bunch of them out?" he wonders today. Allied troops, especially the Russians, were closing in. His flight training ended. He was placed in what he called Air Force Infantry and issued a French rifle of World War I vintage. He quickly exchanged it for a K98 carbine rifle. Later he manned a ME-42 machine gun. He realized, however, that Germany had lost the war. "So one night I quit," he recalls. "I gave one of my buddies the machine gun and I kept my Luger. I said, `I'm going to go home. For me the war is over.'" From the woods he watched Americans on the march, and was captivated by their carefree attitude. "I was lying up there in the bushes and they were just having a good time coming down the autobahn," he recalls. Joachim hid in haystacks during the day and traveled at night. He surrendered to a group of French soldiers who handed him over to Americans. Food was scarce in the POW camp where 500,000 prisoners were housed. "We had one C-ration can and maybe a handful of biscuits a day," he recalls. He discovered something else to eat. "I volunteered for duty because sometimes I would go out and clean up the yard or something and pick up grass and I found out that grass was nice to eat, at least tasteful. So that's where I learned how to eat grass. It was rough for a while," he says. Hearing that German prisoners were going to be sent to work in coalmines in France, he ate soap to get sick. Joachim eventually returned home and became a bricklayer, then a field engineer. He married and had a daughter. His parents divorced, and his mother and sister moved to Houston. Devastated after his wife's death, he immigrated to America, and lived in Houston where he worked as a construction engineer for Farnsworth & Chambers. He joined Clipper Manufacturing Company, a paving company specializing in building interstate highways and runways for air force bases, and was promoted to a general superintendent. Later he moved to Denham Springs, Louisiana. Joachim wrote a book, Glory Denied. He also enjoys re-building World War I airplanes. |