|

|

|

|

|

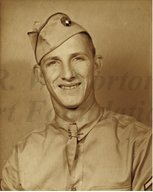

Thomas was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, the son of William Agusta Troegel and Eva Bates Troegel. His father was employed at L&A and KCS Railroad before moving the family in 1926 to Mansfield, where he worked as a machinist at Nabor's Trailer. Thomas enjoyed a boyhood of hunting and fishing and playing baseball. A member of the Boy Scouts, he attended National Jamboree once, and attained the rank of Eagle Scout. To make extra money he mowed yards and worked as a lifeguard at a pool, where he gave swimming lessons to women and children. In recalling the Depression he talks of how his father repaired the holes in their shoes. He says, "Daddy would cut the pattern of the shoes, slip it in. That's what we'd wear." The family kept a garden and raised chickens. He says his mother mainly sewed and embroidered. "Mary raised me," he says of Mary Pratt, a woman who worked in their home. After Thomas graduated from Mansfield High School in 1938 he went to work for Brown Roberts Hardware Supply Company as a traveling salesman, mostly in north Louisiana where roads, made of gravel or dirt, were "terrible." He witnessed episodes of the Louisiana Maneuvers, the large war games that took place in the state near the beginning of America's involvement in World War II. In June of 1941 he married Bennie Jo Hill. They would have four children, nine grandchildren, and several great-grandchildren. Thomas was drafted and sent to basic training at Camp Shelby near Hattiesburg, Mississippi, then to Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he was trained as an artillery observer. He became an instructor in fire commands for 105s and howitzers at Fort Bragg, and also served as a lifeguard at a pool at the fort. While there, Bennie Jo joined him and worked in town. Thomas went overseas from New York aboard the SS Europa, arriving in England in the winter of 1944. He was attached to the 69th Infantry Division as a forward observer, and also spotted for the 82nd Airborne Division. In the Ardennes Forest in Belgium he recalls seeing American dead still in trenches. "They weren't able to pick them up that fast," he says. Although it was very cold, he says the Army gave him "good clothing and heavy blankets." He mainly ate dry rations, but also says they shot and barbecued deer. He received a letter from Bennie Jo "nearly every day. Sometimes I'd get four or five letters at a time," he says. His letters to her were often censored. As forward observer, he directed fire on tanks, troop carriers, railroad cars, and infantry. He stationed himself on the ground, in a building or atop a house, "or anything you could find where the Germans couldn't find you. But never get in a church. That's the first place they go, to a church," he says. At night, he returned to the lines or changed his position. Occasionally, he said, German civilians hid him in cellars from German soldiers who were "were real rough" on civilians. Many other German soldiers wanted to surrender. One emerged from the woods, speaking English, and asking to surrender. "He said, `My friends want to surrender, too,'" Thomas recalls. "I think there were almost 32, 35 something like that, came out to surrender." Once he stumbled into an office in a building where German officers had committed suicide. Thomas was on the Elbe River, about 30 miles from Cologne, and had met up with Russian troops when Germany surrendered. He received a Bronze Star for his service in directing fire from behind German lines. He was also wounded by shrapnel. Thomas sailed to New York and was discharged in October of 1945 as a sergeant. He went to work at Sample Company, a hardware store. He ran his own department store for several years, turned it over to his sister, and became a deputy sheriff. Later he opened Troegel's Grocery and operated the business until his retirement. |