|

|

|

|

|

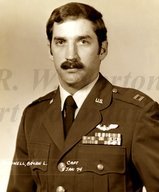

He was born in Saint Vincent Infirmary in Little Rock, Arkansas, the eldest of four children of Woodyard and Ruth Fisher McDowell. His father's exploits as a B-25 pilot in World War II fascinated the boy. "A big part of my military interest stems from just going through all of his trunks and scrapbooks and pulling out old uniforms and hats and trying them on and playing around with them on and pretending that I was flying." Bryan recalls. In 1958 Woodyard, who was transferred often in his work for General Motors, purchased a Chevrolet/Buick dealership in Newport, Arkansas, where Bryan finished high school. Meanwhile Woodyard served as church choir director and sang tenor solos. Bryan took piano lessons, and learned to play cornet, trumpet, guitar, and keyboards. "It was just in the air we breathed," he says of music in the family. He finished high school in 1965, attended Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, then received an appointment to the U.S. Air Force Academy. "I wanted to fly so badly, and I loved the tradition and I loved the history of aviation," he says. Quickly, Bryan says he was "dazzled" by the academy, where he excelled in the military regimen. While there, he and other "Southern boys" formed a rhythm and blues band. After graduation, Bryan volunteered to switch to the U.S. Army and entered helicopter training as part of a group of 16 Air Force pilots. He took undergraduate pilot training at Fort Wolters near Mineral Wells, Texas, then was sent to Fort Rucker near Dothan, Alabama, for advanced training. He finished as the distinguished graduate in the group of 16, and was able to choose among duty stations. He selected a slot in the 40th Air Rescue Recovery Squadron, based in Nakhon Phanom, a Royal Thai Air Base in Thailand, where he would fly the H-53 helicopter, known as "Super Jolly Green Giant." He was sent to Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, Utah, to learn to fly the H-53, but because of wintery conditions, he finished his course at Patrick Air Force Base in Florida. In January of 1972, he went through jungle survival training in the Philippines. In Thailand, he often volunteered for "volunteer-only" missions. Often he flew above 10,000 feet to avoid small arms ground fire and missiles. He felt relatively safe on base, although there were "spies everywhere" nearby. Pathet Lao guerillas often fired on helicopters within five miles of the runway. He recalls getting very little mail. "I was notorious for not writing my family, and I had no girlfriend, no wife. I was really a lone wolf over there," he says, adding that he was "immersed in the mission and immersed in staying alive and surviving the mission and doing the mission." As part of his duties he followed F-4 and F-105 missions, listening to air traffic and ready to pluck from the ground pilots who ejected after their plane was shot down. He calls the Hanoi-Haiphong area, with its radar-controlled missiles and anti-aircraft guns "the most dangerous, hostile air environment in modern history for aircraft." His service came at "the end of the end" of the Vietnam War. "I had feared that I would miss out on the war. Is that irrational or what? I was kind of thinking, `My daddy did it and I had to do it,'" he recalls. He points out that 1972 was the largest part of the air war in the conflict. In one mission, he picked up a "backseater" of an F-4 who had survived 23 days on the ground in North Vietnam. In another, he and his crew earned the Silver Star for a mission called "Bob and Zero Five," on November 18, 1972, when a missile knocked out an F-105 Wild Weasel. The two crewmen ejected, landing on a saddleback ridge within sight of the Gulf of Tonkin in North Vietnam. In the nine-hour mission he called "a miracle," he survived small arms and anti-aircraft fire to rescue the two pilots. He recalls popping up from the ground, through the clouds, to a bright sky. "The sun was high in the sky and the sky was blue and everybody was yelling....That was the height of it all," he recalls. Two weeks later he was back in the States, his tour of duty ended. "In my mind, I was still at war," he says of the quick departure from a combat zone. The Christmas holidays and winter of 1973, "was just a fog for me," he says. The next year he worked with NASA at Patrick Air Force Base and at Eglin Air Force Base, both in Florida. Although he planned a career in the military, he decided instead to enter the ministry. During his tour of duty, he says, he memorized entire chapters of the Bible, that would "get me through my years as a POW," if captured. He began leading Bible studies at the base. On December 22, 1974 he married Jennifer Harris, a schoolteacher. (They would have two children and two grandchildren.) The couple moved to Monticello, Arkansas, where he studied forestry. Later, using the GI Bill, he earned a degree from Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Austin, Texas. Bryan served for eight years as a mental health counselor with the Veterans Administration in Shreveport. As an associate pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Shreveport, he says his "gift" in ministry is "to really help people who are in crisis, people for whom the bottom has dropped out." He still loves music, and listens to many kinds, including monastic chanting. "It gives me peace," he says. |