|

|

|

|

|

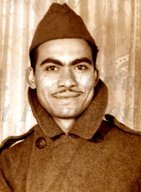

He was born in Hope, Arkansas, as one of 12 children (six boys and six girls) of Henry Walter Ferguson and Lula Hawkins Ferguson. His father, who he says was always active in politics, farmed, and was appointed postmaster for the town of Fulton in the late 1800s, but not without repercussions. "When his wife came there and they found out that he was black, they burned the post office down," he recalls. Federal authorities, however, caught the perpetrators, and made his father a deputy marshal. "He stayed there fourteen years without any more incidents," Randall recalls. Afterwards his father bought a saloon in Texarkana, operated it until prohibition days, then organized a black funeral home. He was also appointed a United States Marshal, a post he held for eleven years. As a youngster, Randall worked on the farm and also in forestry. He and his family were baptized in the Catholic faith in 1933, although segregation kept them from attending the white church in Hope. The priest, however, "came out to our house and set up an altar and said Mass," he says. Randall attended a one-room schoolhouse, then transferred to Yeager High School in Hope, where he quit school in the tenth grade when his father died in 1937. To help support the family, he entered the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), eventually making thirty-six dollars a month. He was stationed at a camp in Bradley, Arkansas, where he built roads for forest fire fighters. He also learned to cook, and soon became head baker at a CCC camp in Smackover. After his stint in the CCC, Randall ventured worked at several jobs in Chicago before enlisting in the U.S. Army on April 8, 1942. Randall was sent to Fort McClellan, Alabama, where, instead of entering basic training, he was appointed to cook for the officers' mess. Two years later he was sent to Camp Polk near Leesville, Louisiana, where he joined the 92nd Infantry Division, an African-American unit with white officers. Afterward the division was sent to Fort Huachuca in Chochise County, Arizona where he was eventually made an assistant mess sergeant of the officers' mess of the 365th Infantry Regiment. He was later appointed to mess for the division headquarters. After a hospital stay from allergy attacks, Randall shipped out with the 92nd on a Liberty ship, the William Mulholland, in a convoy with "about forty ships and destroyers." After a twenty-nine day voyage the vessel reached Italy where Randall spent 18 months as a pastry cook, then later as mess sergeant, in the mess of Major General Edward M. Almond, division commander. As the division drove toward Jena, Italy, Randall often cooked for dignitaries, including Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Mark Clark. While in Italy, Randall enjoyed hearing Wings Over Jordan, a USO gospel group. He also toured Rome and visited the Vatican. The 92nd was in a staging area for the Japan invasion when the war ended. "When Roosevelt died and Truman got to be president, they put that bomb in his lap and he dropped it. That did it," he says. Before coming home, Randall toured Switzerland. "Cleanest country I'd ever seen," he recalls. "Some of the Swiss people had never seen a black person before." Randall sailed home on an eight-day voyage to New York. He was discharged at Camp Robertson in Arkansas on December 2, 1945 at the rank of T5. He quickly saw race relations had not changed in the south when he took the train to Camden, Arkansas. "They had cars for black to ride in and cars for whites to ride in," he says. Married at the time to his first wife, the couple visited his mother in Chicago. He returned to Camden and took over his sister's restaurant, where he stayed for twenty-three and a half years. He was divorced, and then married Lizzie B. Howard on December 29, 1947. The couple would have five children, ten grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren. After a heart attack in 1964, he began working in security at Camden Manufacturing Company. He was later promoted to security supervisor, the first African-American to hold that position at the company. When that firm closed he became the first black deputy sheriff of Ouachita County. After four years in law enforcement, he worked for Highland Resources for twenty-two and a half years before retiring. Of his experience overseas, Randall says, "I wouldn't take anything for the eighteen months I spent overseas. I got a lot of experience over there." In advising young people he says, "If this country needs them, they need to go to try to protect it. It's changed a lot from the time I was there. They had us brainwashed, that we were fighting for our country. I came back here and found out we didn't even have a country." In that manner, Randall refers to the long-held practice of lynching African-Americans, still in existence, even after the war. Later, however, he says race relations "got better because of World War II." He saw that "whites that fought over there with us learned about us, and we learned about them. They learned to respect us for who we were." Randall is a member of the American Legion in Camden, and of Greater St. Paul Baptist Church in Camden. He serves on a tax equalization board, works as a ward committeeman, cooks for his church, and raises vegetables in his one-and-a-half acre garden for sale at farmers' markets. |